In this country with the second highest precipitation rate in the world, around 130 million umbrellas are sold every year, and the majority of those purchased are low-cost plastic umbrellas from China that sell for 500 yen (about 4 USD) a piece.

But while it might seem like the plastic umbrella market is completely dominated by Chinese imports, in the middle that monopoly stands White Rose (Tokyo), the lone Japanese company that still makes plastic umbrellas.

The company has a long history as an umbrella manufacturer, celebrating its 294th year in business this year. In 1958, it created the world's first plastic umbrella. At the time, most in the industry dismissed the product as “heretical,” but it became a huge hit because of a practicality that was lacking in Western umbrellas at the time. In recent years, however, the departure of the production base to China and the adoption of the technology by overseas manufacturers have inaugurated an era of low-price, low-durability imported umbrellas, creating a highly disadvantageous market for domestic makers.

Today, White Rose sells “safe, unbreakable umbrellas” in the 4,000-to-8,000-yen range ($33-$67 USD), with high-end, low-volume production of about 13,000 units per year. Empress Michiko uses their umbrellas at the Enyūkai, an annual garden party frequented by cultural dignitaries, and the company has become famous as a designer of one-of-a-kind articles for the Imperial Family. England's Prince William caused quite a stir when he used White Rose umbrella during a recent visit to Japan.

White Rose prides itself on being the sort of company that has discovered a creative solution for every dilemma it's faced-one that has single-handedly revolutionized the image of disposable plastic umbrellas. But while you might think they've built a stodgy brand identity as the “father of the plastic umbrella,” Sudō Tsukasa, White Rose's tenth CEO, describes their history “a struggle with endless market traumas.”

“It's a history where imitators have shown up whenever we've developed anything good. You could call those ‘corporate traumas, "I think. Along the way we" ve seen a thousand good reasons to stop making plastic umbrellas, but we never have, and that isn't because we have an exaggerated sense of importance as the ‘father of the plastic umbrella.’ We're just attached to our product, and we're tenacious. I believe we're here today because we've stayed attached to the plastic umbrella through all our tough times.”

But why stay committed to plastic umbrellas in such ferocious headwinds? Where did they come up with all of their hit

products? We asked Mr. Sudō to tell us the story.

Postwar “Umbrella Covers” —White Rose is the first company in the world to make umbrellas entirely out of plastic. Where did that idea come from?

“The plastic umbrella grew out of an ‘umbrella cover’ we developed after the war. This started with one of our former CEOs, who'd been imprisoned in Siberia for four years after the war. He had a late start in business, obviously, and he wanted to make up for it by doing.

something nobody else was doing. Umbrellas back then were made from cotton materials. Needless to say, cotton umbrellas got wet easily in the rain; they'd lose their color quickly and drip dye all over people's clothes. But our CEO noticed the plastic tablecloths the Occupying Army had brought with them. We made umbrella covers out of this material. Soon the newspapers picked up on it and it became a hit. We got a warm welcome from retailers too. Umbrellas and covers were sold as sets, which increased the amount we got from each customer.

A while later, though, a new material called nylon came out, and all of a sudden Western cloth umbrellas were replaced with nylon. Nylon was more water-resistant than cloth—all at once, no one needed an umbrella cover anymore.

At that point we realized that plastic was the ideal material to repel water, so we attached plastic directly on top of our umbrella spokes. Then, in 1958, we made our first plastic umbrella. At the time it was impossible to make transparent plastic, so our umbrellas were white. But they never soaked through, and because they never soaked through, they never tore. We needed strong spokes, so we developed spokes along with plastic sheets. All the while we were trying to figure out what a top-notch plastic umbrella might look like.”

“Expelled” from the Industry, Taking on the World

—How were your sales back then?

“We couldn't sell them. The wholesalers refused to stock plastic umbrellas. We attached plastic directly to the spokes, so our umbrellas didn't need the stitching technology behind Western umbrellas. People thought we would shake up the structure of the industry and drive umbrella craftsmen out of business. With no other options available, we scraped by selling our umbrellas on consignment, or on the street. But we believed in ourselves: ‘our umbrellas absolutely never get wet, and the day when that is valued absolutely must come. Some day, we'll cover Japan in plastic umbrellas.’

Then, in 1964, the Tokyo Olympics—the event still remembered as the apex of postwar Japan—opened. Buyers from the biggest umbrella retailers in America came to Japan, where they discovered plastic umbrellas for the first time. Back then, there were no umbrellas in America that used plastic materials, and we thought ‘Maybe these would sell in New York. It rains a lot there.’ We've been exporting ever since. Around that time, we designed a plastic umbrella that covers your entire head and shoulders. Today the Fulton UK sells a style of umbrella called the ‘birdcage.’ This was its ancestor.

But people noticed these were selling well, and soon they started making them in Taiwan, where the production costs were lower than in Japan. We couldn't do about that, so we moved to reclaim the domestic market.”

Plastic Umbrellas as Japanese Fashion—What were the next products you made?

“We set our sights on designing plastic umbrellas with a high-fashion sensibility. In the 70s Japan entered a period of rapid economic growth, and it was hard to miss the way the apparel industries were promoting new fashions to women. People back then had a need to own things that were different from other people, and this was also the era of the first miniskirt boom. And not just everyday women; this was a time when even then-Princess Michiko wore a ‘mini,’ so we designed a plastic umbrella in the miniskirt style. We were still selling on the street in Ginza and on consignment, but we thought if we could have our umbrellas featured on TV they’ d be known all over the country. They cost the same as high-end silk umbrellas, and we printed different colors and stems on them, which attracted a lot of attention as high-end fashion. Behind all that publicity, our transparent, water-repellant plastic umbrellas quietly attracted attention too. The number of shops selling our merchandise started increasing around this time.”

—It must have felt like your dream to “cover Japan in plastic umbrellas” was finally within reach.

“Haha, well…it did and it didn't. A huge number of copycat umbrellas started showing up in the Kansai area, so we created a plastic umbrella manufacturers association. Anybody who joined and paid dues would have the right to use our

production practices. But then a threat appeared from overseas: 500-yet plastic umbrellas from China started taking over the Japanese market. Thanks to those umbrellas, plastic umbrellas became associated with throwaway umbrellas that

break easily, and before we knew it we were the only Japanese maker left in business. We felt that if the

first company to make plastic umbrellas were to stop making them, there would be nobody left making them in Japan at all. In the mean time, to keep the umbrella fire from going out, we started making shower curtains and umbrellas for photo shoots. We stayed in business this way for more than twenty years.”

Made-to-Order Umbrellas for the Political Elite —It sounds like you were in a difficult situation.

“We were, but in the middle of that we started getting made-to-order requests. One of the most successful of those was an umbrella we made for a politician who asked for an umbrella he could use while giving speeches. He wanted a transparent

umbrella, something with a dignified look that would stand up to wind and rain when he gave election speeches from the top of his car, but would still let the audience see his face. The design was based a slight modification of an umbrella

we'd made for the police department, to be used during auto accident investigations. For that umbrella, we used strong iron spokes to fill the order. To symbolize our growing success, we named that umbrella ‘Kateru’ [sounds like ‘we can win'in Japanese] and set its price at 4,000 yen. It started spreading by word of mouth, and soon we were getting lots of orders during elections. Today we've switched the iron spokes to lightweight fiberglass, which we use in a product called ‘Shin Kateru’ [ New Kateru.]”

A Lightweight Umbrella for the Empress—Tell us about some of your other made-to-order

“Well, for example, we have an umbrella called ‘Enyu.’ This was made for the Imperial Household Agency, which asked us to design an umbrella for Empress Michiko to hold during the many outdoor functions she attends. The Empress carries her umbrella on her shoulder in order to keep her face visible; even in heavy wind, she cannot hold her umbrella in front of herself. The request was for a sturdy, transparent umbrella that would allow the Her Majesty's face to be seen, and that would create as little physical burden as possible.

We designed a ‘reverse water dispersal’ umbrella, with holes in the plastic. These holes channel wind through the inside of the umbrella, but do not let rain through the outside. We're very proud of the engineering of this umbrella. We believe our long history as plastic umbrella designers is what gave us the skill to come up with it.”

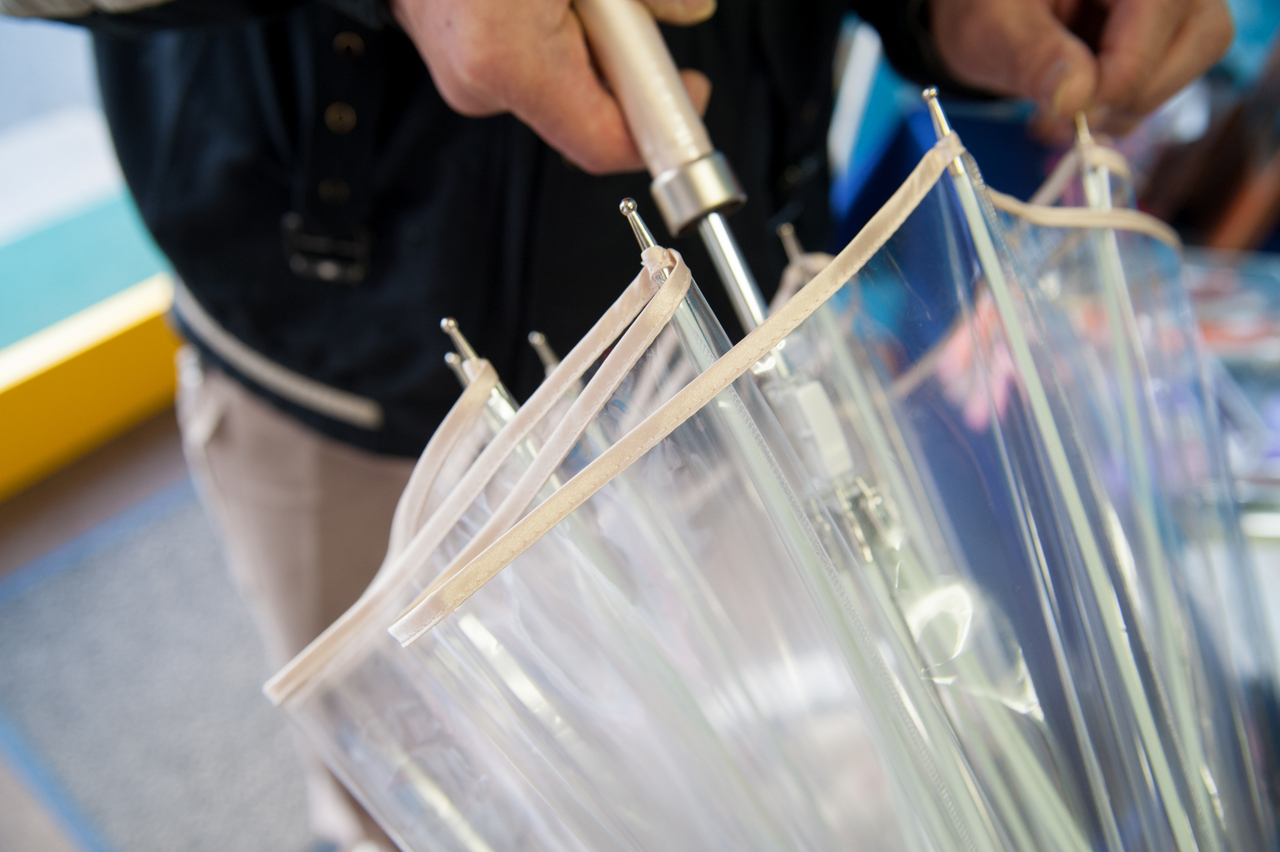

The spokes are made from resin fiberglass with a 3.5-mm diameter. They're flexible and extremely hard to break, and they absorb most of the force of the wind. In addition, we use a specialized manufacturing process to layer three sheets of plastic on top of each other. Normally, if an umbrella gets the plastic will stick to itself, but Enyu's unique layering process keeps the sheets from sticking together. We used a lot of subtle design techniques that aren't noticeable just by looking at the umbrella. At 8,000 yen it's definitely not cheap, but a lot of people have ordered them as wedding gifts. It's become a product that meets a lot of different needs.

—Is part of Enyu’ s appeal the fact that it looks like a regular plastic umbrella?

“The Empress expressed a desire to lose her feeling of distance from ordinary people. From far away Enyu looks no different from an umbrella you'd buy in a convenience store, but if you look carefully it’ s not quite the same. In the end, though, it's still a plastic umbrella, and there's a lot of meaning in that.”

“We want to design an umbrella that will protect its owner”

—Were there any changes in the normal orders you received while you were

designing all these special-request items?

“Well, our concepts have changed, so our umbrellas have started being featured on television and in magazines, but lately everyday customers have started buying them too. One of our guiding beliefs today is the need for an'umbrella that will defend its owner.’ An umbrella should protect its owner from the minute they go outside to the minute they come home. If it breaks along the way, the umbrella might as well have abandoned the person who bought it. When an umbrella isn't well made, it blocks its owner’ s view and turns into an obstacle that limits its owner’ s mobility—and this is even harder for the disabled, or for people with small children. When people go out in the rain they want to be able to see people coming and going when they look around, so they need to be able to see through their umbrellas. When we asked ourselves about what sort of product does the best job of defending its owner, we realized it was an umbrella designed for a single user. A regular umbrella can only withstand winds up to 10 meters per second, but ours won't break under winds up to 20 meters per second, so they create a much stronger feeling of safety. They almost never bend or break, and even when they do we have the parts in stock

and can easily repair them. That's one major difference between our products and a standard plastic umbrella.”

—What sort of umbrella would you like to make in the future?

“We want to keep on doing what we’ ve always done— dare to make the kinds of umbrellas no one else is willing to. That may mean umbrellas that don't sell in high volume, or that aren't easy to make, or that need to special care when you're finished using them. Our rivals are weak in those areas, so we want to keep working in them. In 2020 the Olympics are coming back to Tokyo, and ‘Made in Japan’ will be in the global spotlight again. Since the last Tokyo Olympics we’ ve accumulated 60 years of history as umbrella makers, and we want to believe a future is coming when plastic umbrellas will be regarded as one of the traditional crafts of Japan. When Japan's traditional craftsmen are not valued for what they provide, young

people lose interest in what they do, and the craftsmen have a hard time finding new apprentices. What cultural contributions do we make with our plastic umbrellas? That is a question we’ re always asking ourselves.”

Written by Tatsuro Negishi

Edited by IGNITION Staff

Photos by Daisuke Hayata

Translated by Michael Craig